(I submitted this article to a military history magazine and they said it was too controversial.)

When considering the wartime role of the 99th Fighter Squadron and 332d Fighter Group, it is essential that it must be interpreted in the context of the time and the historical role rather than as an instrument of social change with the attitudes of even the 1960s, not to mention those of today. While the young black pilots who trained at Tuskegee Army Air Field and were subsequently assigned to the 99th and 332nd saw combat, their effectiveness must be considered in relation to the military role they were sent overseas to fill rather than wishful thinking and hero worship. Their children and grandchildren have as much right to be proud of their accomplishments as any but to exaggerate those accomplishments as is so often done does them and their memory a great disservice.

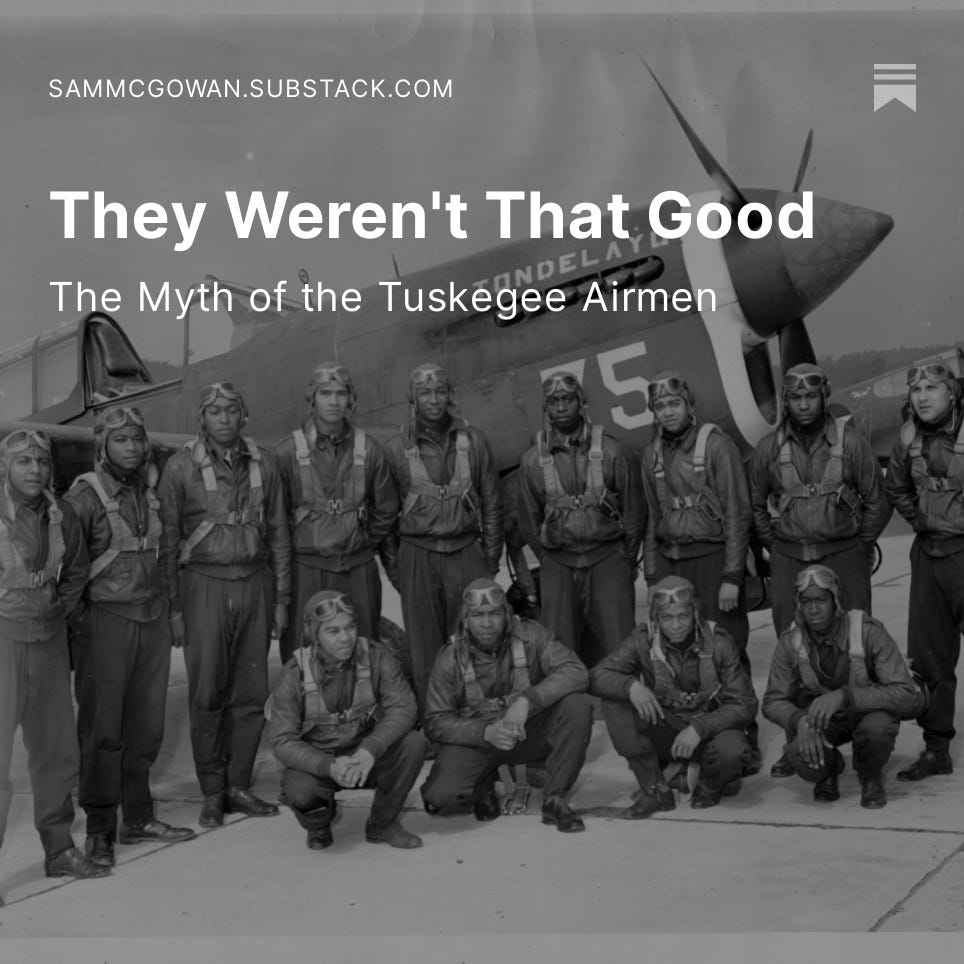

Ask many Americans today about the Tuskegee Airmen and they will tell you that they were a group of Negro airmen who proved their critics wrong and became "one of the best" fighter groups to fight in World War II. (The term "African American" did not come into use until the 1980s.) Such an assertion is half-right; the men who were part of the 332nd Fighter Group and the 99th Fighter Squadron were Negro airmen. (American Indians, Asians and Hispanics were not considered "colored" and served in regular units.) As to whether or not they proved their critics wrong is open to debate, but there is nothing to prove the assertion that they became one of the best fighter groups to fight in the war. In fact, the general consensus of the senior officers under whom they served was that they were the least effective in the theater rather than the best. Another oft-quoted remark is the assertion that the men of the 332nd were "so good that they never lost a bomber," which is simply untrue. That at least some of the young colored airmen who won their wings at the Army Flying School at Tuskegee, Alabama became competent airmen is a fact but their record in combat is hardly spectacular.

Prior to activation of the 99th Pursuit Squadron in late 1940, there had never been a colored squadron in the US Army Air Corps or the US Army Air Service which preceded it. Colored units had existed in the United States Army since at least the War of 1812 when colored militia units from New Orleans fought in the battle at Chalmette Plantation, a battle that literally changed the course of American history. Colored regiments commanded by white officers were organized during the Civil War and continued in service afterwards - in fact, colored troops fought on both sides.[1] The "Buffalo Soldiers" of the 9th and 10th United States Calvary were organized immediately after the Civil War, as were two regiments of colored infantry, and saw service on the frontier, particularly in West Texas, and in the Spanish-American War. Colored regiments and divisions continued in existence through World War II. However, despite pressure from civil rights activists and progressive politicians, the US Army refused to activate colored aviation units or to accept colored soldiers in existing aviation squadrons during World War I and in the years that followed. In the 1930s civil rights activists put pressure on the Roosevelt Administration to force the Army to train Negro pilots but the War Department resisted on the basis that the Air Corps was too small to have separate facilities and the law of the land prevented integration of existing units. In a move to placate civil rights activists and the Negro press, in April 1939 Congress passed Public Law 18 which stipulated in part that aviation training would be provided at government expense to young Negroes. While the Army was trying to decide how to comply with the law, the Civil Aeronautics Administration authorized training of Negro pilots through the Civilian Pilot Training Program, a government program to provide private pilot training to students, women as well as men, at airfields in close proximity to college campuses - including Negro colleges. With the adoption of the law, the Army Air Staff realized it was going to be forced to establish colored squadrons and began making plans to do so, although it took more than eighteen months before a plan was developed and approved by the War Department. In the meantime, World War II broke out in Europe and although it was still technically neutral, the US began gearing up for war.

In October 1940, in a political move designed to attract Negro votes in the upcoming presidential election, President Franklin Roosevelt announced that Negroes would be trained to become military pilots. A few weeks later, in November, the Army Air Corps notified its Southeastern Training Command to prepare to train colored pilots at a new school that was to be established near the Tuskegee Institute, a famous Negro college that had been established in the late Nineteenth Century at Tuskegee, Alabama. Several authors have attributed the decision to accept Negro applicants to a lawsuit filed by the NAACP on the part of a Negro applicant, one Yancy Williams, but the suit wasn't filed until early 1941 and by that time the decision had already been made. Williams evidently applied for pilot training and was temporarily rejected because the Air Corps had not commenced the training program for Negro pilots as yet. The suit was withdrawn as quickly as it was filed but many Tuskegee Airmen fans and even some veterans have come to believe that it somehow influenced the Army to act. In fact, the suit was filed one day, and the Army announced the activation of the 99th Pursuit Squadron the following day, which is not enough time for the Army to have even been notified that such a suit had been filed, let alone act on it. Regardless, the Army had already begun the process to begin flight training of colored officers and cadets at Tuskegee before the suit was filed.

Civil rights leaders and the black press were incensed at the choice of a location, which lay in the heart of the segregated South. The leadership of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was not fond of the all-black school and its policies that advocated that young blacks should persevere in society through education rather than through legal action and political activism. Nor were they happy that the Army decided to establish separate colored units; their goal was full integration of the armed services, starting with the Air Corps which was the smallest of the services. That the Army elected to establish a colored squadron did not fit with NAACP goals, while the choice of Tuskegee further infuriated civil rights leaders and some elements of the black media. Their opposition so infuriated Air Corps Commander Brig. Gen. Henry H. Arnold, who favored a gradual approach to integration, that he commented that it appeared that black leaders were "willing to sacrifice the whole program" if they did not have things their way.

The Army originally attempted to follow civil rights leaders' recommendations that a training school be established close to Chicago where the civil rights movement was centered, but harsh winter Chicago weather coupled with the high cost of land on which to build a flying field caused the Air Corps to look elsewhere. The leadership at Tuskegee Institute, which had already established flight training under the Civilian Pilot Training Program, was eager to have the school located there. At a meeting held in Tuskegee of the Rosenthal Foundation attended by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who was a board member, an appropriation for a loan of $100,000 to the school to build a field was approved. (It was during this visit that the First Lady was photographed in a Piper Cub with the chief instructor for the Tuskegee CPTP program in the back seat.) The new field was not a US Army facility per se but was actually a civilian contract training school that provided basic military flight training for colored applicants. There was one difference - once they had graduated from flight training and won their wings, the new pilots would remain at Tuskegee for advanced training as pursuit pilots and their new unit would be stationed at the new military field that was being constructed nearby. The country was not at war at the time and no plans were made to send the squadron overseas. All of the colored cadets were destined to serve with the new 99th Pursuit Squadron which activated at Chanute Field, Illinois in early 1941 then transferred to Tuskegee after an initial cadre of aircraft mechanics and technicians had been trained. Chicago civil rights leaders had pushed Chanute as a training school for colored soldiers, but the Army followed the advice of a number of Negro educators who felt that to bring large numbers of young Negroes into a predominantly white rural area could lead to racial problems. Tuskegee was - and still is - a predominantly black town in a region that is largely black populated and would be less likely to be affected socially by the establishment of a training base for colored troops. The institute dates back to shortly after the Civil War when it was established to provide higher education to the children of former slaves. An initial cadre of colored soldiers was sent to Chanute to train as aircraft mechanics and other support personnel then once they were qualified, they moved to Tuskegee to train others and staff the newly activated 99th Pursuit Squadron.

The establishment of the school and squadron came to be known as "the experiment" as at least one purpose was to determine if colored aviation units would prove beneficial to the national interest. The choice of Tuskegee was initially opposed by Judge William Hastie, a black political progressive and civil rights activist who had been appointed as a special advisor to the Secretary of War on issues related to Negro troops. Hastie's goal was full integration of the Air Corps and ultimately, of all of the military, and he saw the establishment of the new squadron as a step in the wrong direction. He was further incensed at the choice of Tuskegee as he was not in tune with the school's philosophies. The NAACP and the Negro press were less than enthusiastic about the Air Corps' plans. For several months the Tuskegee trainees were generally ignored by the black press, except for sarcastic comments such as a reference to them as "Lonely Eagles" in a takeoff on Charles Lindbergh's nickname in an assertion that they would never see operational service. It wasn't until the national press published several articles relating the Negro airmen's progress that the NAACP and the Negro press began to gradually give them favorable publicity.

To command its first colored squadron, thee Army selected Captain Benjamin O. Davis Jr., a West Point graduate and the son of a career Army officer who had grown up in the military.[2] Davis' father was the Army's first Negro general officer. He became a member of the President's Advisory Committee on Negro Troop Policies when it was established in August 1942. At 29 years of age, Captain Davis was actually past the maximum age for Army flight training, but requirements were waived for him to become part of the program. Davis initially failed the flight physical but was admitted to the program anyway due to the need for an officer with his qualifications. He was the only commissioned officer in the class of thirteen men who began training at Tuskegee in October 1941. Eight cadets washed out, but Davis and four cadets completed the program and were awarded the silver wings of US Army pilots in March 1942: the cadets received commissions as second lieutenants. The new officers were immediately assigned to the 99th Pursuit to train as fighter pilots while Davis was assigned to the base staff. Lt. George "Spanky" Roberts, who had been a member of the first class, was placed in command of the squadron on June 1. When the men entered flight training the nation was still at peace and Army plans were only for one squadron, but war broke out in December and created a need for more pilots and aviation personnel, so the War Department expanded its plans. Instead of one colored squadron, as the nation mobilized for war the Army decided to establish four colored pursuit squadrons, to organize an all-colored pursuit group and to also establish a medium bomber group made up entirely of colored personnel. Some sources have said that plans also included a colored troop carrier group but no mention of such a plan is made in Army publications or in most of the information available about the colored airmen. There were recommendations to commission Negro civilian pilots as service pilots to serve in the Air Transport Command in Liberia but as far as is known, no Negroes served as service pilots although some colored civilian pilots became liaison pilots assigned to colored infantry and artillery units.

When the first class graduated, General Arnold immediately directed that the 99th Pursuit Squadron would become operational as soon as possible and sent overseas. The Air Staff dedicated the squadron to the Liberian Task Force, which at the time existed only on paper, a force to be made up of mostly colored units that would deploy to the African country of Liberia, a nation that had been established by Negro Americans, some of whom were freed slaves, who migrated to Africa in the 1820s. In 1942 Africa was still a contested continent and the British had yet to gain the upper hand against German and Italian forces north of the Sahara. A second squadron, the 100th Pursuit Squadron, would also be activated and deployed overseas, although no destination was as yet specified. Wartime plans were also made for an entire group with three fighter squadrons and eventually the 100th was earmarked to go to it.[3] Immediately after winning his wings, Davis was jumped a rank and promoted to lieutenant colonel and appointed chief of personnel for the newly established Tuskegee Air Base. Lt. George Roberts was given command of the 99th from June until August 1942 when Col. Davis assumed command. Several dates were set for the squadron to move to Liberia, but the movement was delayed when it became apparent that the need for a fighter squadron there was decreasing and was eventually canceled.

Turning the 99th into an operational squadron presented some unique problems. It was intended to be an all-colored unit and although white and Puerto Rican officers could participate in the training, once it became operational the squadron staff would be made up entirely of colored officers. While Davis was an experienced officer, his aviation experience consisted only of basic flight training while Roberts was both a new pilot and newly commissioned. The same was true of the flight leaders. Except for Davis, the 99th's officers had to gain experience as officers and aviation experience at the same time. Normally, an Air Corps or HQ Air Force squadron consisted of experienced officers to serve in key positions such as squadron commander, operations officer and flight leaders, but there were no experienced colored pilots to draw from and the end result was an operational squadron lacking in both aviation and leadership experience. After the 100th Fighter Squadron activated, it also drew on the newly commissioned colored pilots, whose numbers were less than anticipated due to the high wash-out rate among colored cadets. The wash-out rate at Tuskegee was more than 50%, at least in part because of the reduction in Standard Nine - commonly called "Stanine" - test selection standards for Negro cadets. While the minimum score for white cadets was 6, it was reduced to 4 for black applicants. That all of the initial classes of new pilots were to become fighter pilots also presented problems. In the normal Army Air Corps training program, pilots were assigned based on ability, with the most aggressive and proficient pilots going to high-performance fighters while the rest went to bombers, transports or light liaison aircraft. In 1942 there was nowhere for Negro pilots to go but into fighters, except for a few slots for observation pilots with colored infantry divisions that were being trained.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tennessee Flyboy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.